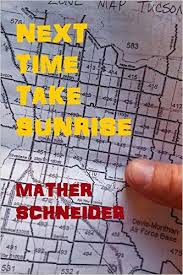

The following stories are from Mather Schneider's collection of short stories NEXT TIME TAKE SUNRISE (2015) available on Amazon:

THE DOUBLE

132 W. JACINTO, APARTMENT 6

I pull my cab up to 132 W. Jacinto and park. Rosalita Morales is 23 years old. She has big lumpy formations on her left arm where they have inserted needles and tubes for her kidney dialysis 3 times a week, for years and years and years.

“Morning,” I say as she climbs in the cab. She has dark skin and eyes, skinny.

“Yes, I guess it is, isn’t it?” she says.

I take her to a doctor on the east side, which is different than her usual place: the dialysis center. She is inside the doctor’s office for only about 30 minutes. I wait for her in the cab.

When Rosalita comes out she’s crying.

“Oh, shit, shit,” she says in the cab when we were on our way back to her apartment.

“Bad news?”

“You see this?” she says, referring to the lumpy formations on her left arm, on the opposite side of the elbow. “That fucking doctor says there’s clotting going on in my arm and we have to use the other arm! That’s all I fucking need.”

She looks at her right arm, her good arm. It is smooth and thin, beautiful. She strokes it a couple of times and then looks at the ruined cauliflower of her left arm.

“Either my right arm or one of my legs,” she says. “Those are my choices. I’m gonna look like more of a freak than I do already!”

“You’re on the organ list, right?”

“Yes, but I just got on that list not too long ago.”

“But you’ve been on dialysis for years.”

“3 years ago, when I was 18, my mother gave me one of her kidneys. You can live with only one.”

“Yes.”

I turn left on Congress, right by the statue of Poncho Villa on his horse. The horse is rearing with its two front feet in the air and a fierce look on its face, which mirrors the look on Poncho Villa’s face.

“Well, 3 months into it everything was going fucking great! Then, I stopped taking my anti-rejection drugs.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know, I really don’t know, but my body rejected the...my mom’s...kidney.”

“That’s rough.”

“So, it was kinda my fault.”

“Yes.”

“I was in the hospital for 3 months, I almost didn’t make it. So, now I’m on the list again, but they didn’t want to put me on it for a long time, because of all that, but they finally did anyway. I had to go through like a million fucking psyche tests. My mom was real mad at me.”

I take a left at Grant Road and miss the yellow arrow just barely. I feel the camera flash through my windshield and know the automatic cameras have caught me running the light. The ticket will appear in the company’s mailbox within 10 business days. I will get the ticket and a lecture and will have to pay 134 dollars to the courts. I’ve already had 2 others. One more and I’m gone.

“My brother said he would give me one of his kidneys,” Rosalita says. “But, he’s skeptical. I can’t blame him.”

I pull up to her apartment and she climbs out.

“Thank you so much,” she says.

Her face is as sad as an old heavy sunflower, dried seeds falling to the ground like teeth.

CORNER OF 36TH AND COUNTRY CLUB

I know I shouldn’t stop the cab, I should just keep on driving, but I need the cash. The neighborhood is shitty but it’s still early, only 10 o’clock a.m. Two guys are standing at the corner where the mini mart is, waving at me. 2 young Latino-looking males, dressed in price-tag-still-on baggy pants and big long shirts. The police don’t need to profile, people profile themselves by being so needy for approval. They can’t resist looking the part.

I stop the cab. They get in the back of the cab before I really know what’s going on.

“12th and Valencia,” one of them says.

They both scrunch way down in the seats.

“I’m gonna need the money up front,” I say. “That’s a long way.”

“Just drive.”

“Not without the cash, man.”

He opens his wallet and flashes it at me. It’s loaded with bills. Then he puts it away again.

“I need the money in my hand. 30 bucks.”

“I ain’t giving you shit, man,” he says, and gives the other guy a fancy handshake. They both laugh.

“Then you’re not going anywhere, get out.”

They look at me with a hatred that seems far greater than is warranted. The quiet one jumps out and starts walking off. From the way he walks it is clear he’s drunk. The other one just sits there.

“Get out.”

Finally he sits up and opens his door and slowly puts one foot down on the pavement. Then, as I turn back towards the front, he leans into the cab again and swings his left hand over the seat and hits me on the right side of his face. It stings, swells up immediately. My pride is shattered, and I’m dizzy for a few moments. The kid laughs and struts slowly off to his friend. I drive out of there feeling very lucky, and unlucky, at the same time.

2550 NORTH ORACLE, APARTMENT 6755

Some of these apartment complexes are as big as villages and as confusing as LSD labyrinths. It’s a medical voucher, Charlotte Bercher. Her apartment is 4512. After 15 minutes I find the right building, and then begin looking for the apartment. There she is waving at me, walking down the sidewalk. Middle aged white lady, like a sun-bleached eggplant.

“How you doing today?” I say.

“Oh, not so good. It’s getting hot isn’t it? I almost feinted.”

“Yes, very hot here in the summertime.”

“I wish my neighbor would give me the money he owes me,” she says. “He owes me 5 dollars. I’ve got to do laundry. The office has a machine and you put the money in the machine and it puts the money on this card and you use the card on the washers and driers.”

“Ah.”

“I don’t have any money on my card now. All I could do was wash my towels, I couldn’t dry them.”

“Why don’t you hang your towels out to dry in the sun?”

She looks horrified at the idea and gives a scoff. “Ha! I mean, I’m not prejudiced or anything, you know, but, the, er, the Mexicans are always doing that, hanging their clothes out like that.”

“Makes sense to me,” I say. “It’s free, it’s natural.”

Charlotte receives a government check every month and her basic needs are taken care of. She is safe and secure as a hamster in a Coca Cola cup.

“I don’t like scratchy towels,” she says.

“And that’s your right.”

“Towels get all scratchy if you dry them in the sun.”

“Yuck.”

“Oh, yes,” she says. “Plus driers are faster.”

Her days are narcotic run-ons of soap operas, rape fantasies, grilled cheese sandwiches and country music. Every once in a while she gets lucky and has a doctor’s appointment.

“Do you know I signed up for the George Straight fan club?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“But that bastard never sent me anything, not even a hello.”

“People are rude these days.”

“Hmmmph.”

She has a 12 o’clock appointment. Colon exploratory probe.

“I haven’t eaten since yesterday,” she says. “When you take me home later can we stop at We Went Wongs?”

“Maybe.”

“I’ll buy you a coke.”

“Ok.”

I drop her off and head out. I take a big drink of water from a bottle that was frozen in my freezer all night, and now thawing slowly. It’s as cold as glacial run-off on my lips and throat.

1280 SOUTH VISTA DEL MONTE

I decide to work a double shift, so when the sun goes down I’m still out here. The night goes slow for a while. Then about midnight I get caught in a gun fight outside a frat party. Some gang members invade the place. A couple of college girls jump in my cab. They are not the girls who called me to come get them, but I don’t care and I get out of there with some bullets zinging. It’s confusing and scary and the girls are crying and cussing and one of them is very drunk.

When I get them to their sorority house, the drunk one opens her door and does a face-plant on the sidewalk. She is complete dead weight. Me and the other girl lift her up and drag her to the front door of the sorority house. The passed-out girl is wearing a dress and the dress rises up to her waist. She has yellow thong panties and orange waxed legs.

The fare is $14.50. The girl is annoyed when I ask for money. She gets a twenty out of her 200 dollar purse.

“Just give me back a 5,” she says.

I keep the 50 cents and save it for the future.

THE PEARL NIGHTCLUB, ORACLE AND WHETMORE

A drunk guy drops a hundred dollar bill on the floor of the cab when he gets in. I reach down and gather the bill up in my fingers as the drunk guy turns to look at a woman who walks out the door of the nightclub.

281 WEST LAGUNA

It’s almost 6 o’clock and I’ve worked for 24 hours straight, which is technically against the rules, but there are ways around the rules. Just when I’m about to go home, I get another call for a nearby address. One more, why not. I drive over. A young white kid comes out of the house dressed in what looks like a restaurant uniform. It’s early but the sun is well up.

“The FURR’S restaurant on Saint Mary’s,” the kid says.

FURR’S is a local family restaurant. I head west on Saint Mary’s Road.

“Going to work, eh?” I say. I figure the kid’s a breakfast waiter at Furr’s.

“Yep,” the kid says.

Tucson is waking up, but I am drowsy, and nearly done. How many years of this? How many years more of it do I have, can I take? I’m 47 now, been doing this for 14, have no plan for retirement, haven’t paid taxes for a long time. Dues, yes, but taxes, no.

When they get to the Furr’s restaurant, the meter says $20.85. I turn around to tell the kid the amount and the kid is already out of the cab.

“I gotta get the money from inside,” the kid says.

He goes inside the restaurant, which looks empty.

“Shit!”

I jump out and run after him. I open the door and goes inside. A couple of waiters are standing behind the counter, another is setting the tables. There is the sound of a vacuum cleaner and it smells like potatoes and onions frying.

“Did you guys see a kid come through here?”

They both nod and point to the other door on the other side of the lobby that leads outside.

“He doesn’t work here?” I ask.

“We’ve never seen him before,” one of the waiters says.

I run to the other door and go outside into the early morning. I see him now, way down the block, running. I can’t catch him and really I wouldn’t want to find out what would happen if I did catch him. I stand there and watch him run. Go, man, go.

I’m breathing heavy, but it slowly goes back to normal. I know I won’t be able to sleep now and I don’t feel like going home. I go back inside the restaurant and sit down in a corner booth and look at the menu. I’m the first customer of the day.

PLASMA

A pigeon pecked at his left ear and woke him up. He had slept in the city park last night, for the tenth night in a row. He shooed the pigeon away. “Little fucker,” he said.

It was dawn and he slowly got up, got his things together in his small green bag, and walked to the plasma bank as the sun was rising. He was tall and thin, with raggedy clothes. His name was Anthony Moore.

By the time he arrived at the plasma bank, a line had already formed outside the door, though the place wouldn’t open for another hour. It was summer in Tucson and already 82 degrees.

The people in line, all men, all a bit cracked, knew each other. They were regulars. The loudest talker leaned against the

plasma bank door.

“I like to get here early,” loud talker said. “I get up early anyway, and there’s no particular point in staying home.”

A nod of agreement meandered among them, somnambulists in the building’s shade.

“I don’t sleep,” he said. “I just don’t sleep.”

One tooth was missing in the middle of his sticky, praline mouth. He had a black shirt tucked into a pair of black jeans. On his leather belt hung a small knife, a pager, two cell phones and a tape measure. Dark sunglasses and a blue brimmed cap pulled low. He was well versed in a variety of subjects, from nano-probe technology to crème brulee.

An enclave of bums staggered by, walking so close together as to be holding each other up. The boniest of all struggled to push a grocery cart, pregnant with bulging, ready-to-burst bags of aluminum cans. The morning sun caused the whole thing to explode with sparkles, like a jeweled tumor.

The bums stopped and one of them leaned into the garbage can. Garbage flew out like a fountain onto the ground all around, onto the sidewalk and street, and every once in a while his hand would emerge with a bit of some abandoned eatable, or an aluminum can, and relay it to one of the others.

Anthony and the others watched the cop car pull up.

The one with his head in the can came out. His mustache was white from the last of someone’s tossed latte.

The cops scolded the bums. One of the bums, the matron, crab-stepped around in circles, picking up all the trash and throwing it back into the can. The cops cocked their heads like robots, bored and cruel with protocol.

The metal gate that protected the front door of the plasma bank was opened 10 minutes late.

“Grace is running late again.”

“No, it’s Thursday.”

“Monica, then.”

They single-filed in, blinking in the gag-clean air, everything white as an egg, cold as a meat locker. A pecan-skinned Hispanic girl in a white frock gave everybody a little silver bag of juice to drink while we waited.

“Morning Monica.”

“Morning, morning...”

It was nice of her.

They committed their names to the paper on the clipboard on the counter, and turned to negotiate the grid of blue plastic chairs. When they each found a suitable spot, they sat down to their juices, as if they were exhausted.

A television was mounted in the upper corner of the room, a bird cage from which squawked the dippy hosts of a morning show. The hosting duo consisted of a taffy-handsome, effeminately enthusiastic, mid-aged male, and a slightly thickened, puritan female, erect as a fence post, with a mouth like a rubber band that tried to talk intelligently, but always snapped back into an automatic, moronic, hominy-toothed smile.

A white-frocked girl with parboiled hands gripped the clipboard.

“Anthony Daugherty?” she called.

Anthony got up from his chair. He stood up and walked over toward the girl who was calling my name. She was plain looking, smooth skin, faint purply smudges beneath her coffee eyes. She took my mug shot and instructed me to go sit down next to another woman in another white smock.

All the employees looked so bored, so resigned, like old circus animals.

Anthony sat down in front of the other lady.

“Give me your finger,” she said. She pricked him with her little pricker, the bitch, then milked the scarlet blood out into a tiny tube. The machine did the rest. Machines did

everything, everything important. The humans served to fill in the blanks, to act as connectors. He hated to see people who have been doing a job so long they have become like a machine. He had been a machine for years and years.

“We have to check your blood for proteins,” the woman said, not looking in his eyes, “and make sure you’re not diabetic.”

She stared at the computer screen, immersed in what she saw. Never was seen anything like this. The screen was swiveled so he couldn’t read it, but a red hazard light blinked on and off, he could see it reflected in her eyes, which were screwed up until her muddy black eyeliner cracked. Her mouth moved in a silent series of puckers, lip-chews, and clucks.

No trouble, please no trouble.

His hands were clammy as frogs’ butts. The air in the building maintained a steady 64 degrees, to keep the germs down, to keep the blood from spoiling. He didn’t see a single fly, in fact, while he waited for the truth.

Finally she stopped looking at the screen, and wrote something down.

“Well?” he said.

“Looks good,” she said. Just like that.

Then there was another wait, another corner, another set of

chairs, this time red chairs.

“Anthony?” the doctor said.

He was short, and a fitness addict. There was not enough fat on his body to fill a blood vial. His musculature was that of a triathlete on heroin. There was black stubble on his suntanned arms where he had shaved them. His black hair was parted over his left eye, with each hair combed back on either side, where they remained, obedient as Mormon wives. His whole head looked like a wood carving.

He knocked Anthony’s knees with a rubber hammer, listened to his heart with his safe-cracker stethoscope, probed his stomach and kidneys, waiting for him to yelp.

He kept writing things down without saying a word.

“Everything ok?” Anthony said.

“Fine, fine,” the doctor said. “Most of the major tests will take a week to come back, so I can’t say much until then.”

“Oh,” Anthony said. “I can still give plasma today, right?

“Yes,” the doctor said. “If you’re sick we’ll contact you, and your plasma will be destroyed.”

He wrote something down, then stopped. “The tests take a week, and if we find something like Aids, we send it in for a secondary test, which takes another week.”

“Two weeks.”

“I made the mistake of telling a guy once, last year, that he had Aids,” the doctor said, “and then the secondary tests came back and it turned out he really didn’t have it. I felt terrible. I drove over to his address as soon as I found out, but he wasn’t there. He’d already moved.”

“Oh, boy.”

“He moved the day after I told him.”

“Ever find him?”

He shook his head no. Then he seemed to snap back and remembered where he was.

“No tattoos?” he said, his pen poised.

“No.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing.”

“Not even a dot?”

“A dot?”

They looked at each other.

“Have you had sex with a prostitute within the last year?” the doctor said.

“No.”

“Have you been incarcerated within the last 72 hours?“

“No.”

Then Anthony got to pee into a cup.

“How much you want?” he said to the doctor as he took the cup.

“Anything,” he shrugged.

When Anthony was done the doctor snapped on a rubber glove and the piss was analyzed in about ten seconds. He walked back over to the desk, signed one more form, and then sent me to wait in another place.

“Everything ok?” Anthony said.

“Just one thing,” the doctor said. “Your crits are a little high.”

“My what?”

“Your crits. Tell the nurse they were a little high. She’ll know.”

“Is that bad?”

“99 percent of the time, no.”

“But I should tell the nurse?”

“Tell the nurse and she can keep an eye on it,” the doctor said.

“Crits a little high,” Anthony said. “Got it.”

The chairs in the next room were yellow.

“Anthony?” the lady said. Another clip board crier. They all wore white smocks, like snow people, snow-royalty. It was colder in each room. She flattened her clipboard against her chest and looked at him. He stood up.

“My crits are a little high,” he said.

“How high?” she said.

“He didn’t say, just a little high, he said to tell you and you’d know.”

“Ok,” she said.

“Is that bad?”

“No problem.”

He followed her into the main room. He had passed a high security clearance test and was finally allowed to see the nerve center. It was like the inside of an alien space ship, with human specimens prone on large gray recliners, looking drugged and hauntingly mollified. The lady led Anthony to a futuristic recliner. It was gray and heavily padded like the others, and curved like a fallen S. He climbed on, happy to relax. It was the most comfortable chair he’d sat in in years.

The recliners were set along the walls of the room, facing one another. He looked at the people. Everybody kept gripping their fists, gripping and gripping.

“First time, eh?” the nurse said to Anthony as he lay there. She looked like a trucker’s wife, with a deep voice, a twisted nose, and strong shoulders.

“You just lie right here, there’s nothin’ too it,” she said. She walked around attending to others. Then she swung back to Anthony’s bed/chair.

“Just relax,” she said. “I’m not gonna stick you yet, Marcela will do that. Which arm do you want to use? Doesn’t matter?”

She wrote something on his chart, tossed it on top of the machine. “Ok,” she said. “See those lights there?” She indicated the machine to his right. “You want them to be green. Except when they’re red.”

“Green except when they’re red.”

“Right,” she said. “When they’re red don’t worry about it. But when they’re green you pump your hand, keep pumping and pumping, ok?”

“Keep pumping.”

“Make sure they stay green, all of them, not 2 or of them, all 4.”

“What about my crits?”

“You just let me worry about your crits.”

She walked over and unhooked a bottle from another person’s machine. She wrote something with a black marker on the bottle and without looking at Anthony she kept talking.

“This is what your plasma looks like,” she said. “Looks like apple juice.” She walked the bottle over to a man who took it away behind a wall. She walked back over to me and slapped Anthony’s machine the way a mechanic would slap the hood of a car. “Your blood goes in here, is separated into plasma here, and then drips down through this, and into this bottle.”

He looked at the empty bottle.

“She’ll make some noise,” she said, “but don’t worry about it, a few beeps and hums means she’s working right.”

That machine was like a combination of R2D2 and Dracula.

“And when you hear her make the charge call,” the nurse said, “Doot-doodooDOOO! That means you’re done. Any questions?”

He shook his head no.

“Ok, then.” She clapped her hands. “Marcela!” She rushed off and a girl the size of a professional wrestler went over. She looked at Anthony’s chart and prepared her sadistic works.

“My crits are high.”

“I know,” she said.

She knew.

The thought of a needle can send people into a panic. It’s as if you can feel that needle going all the way up through your arm and past your elbow and shoulder and into your heart and then even lower. Anthony knew a boy who jumped into the lake, feet first, and landed on a sharp, broken tree trunk, submerged below the water, which pierced his heel and traveled up his leg like a large splinter, all the way to his hip. Needles: nothing should be that sharp.

Marcela busied herself with her clamps and hoses and scissors, her tongue hanging out the side of her mouth, like she was hot-wiring it. She applied iodine with a Q-tip, which was the color of grasshopper spit, in slowly widening circles onto the soft belly of Anthony’s thin right arm.

The scary part about needles is by the time you feel them they’re already in you. Bullets are the same way, but

much worse, Anthony knew that. Even if you watch it happening, it’s like watching a baseball player swing the bat while sitting in the nosebleed seats: you hear the crack a second later, and your senses seem to by lying to you.

Anthony gripped his hand.

There was a guy to his left. His machine was obstructing his face. All Anthony could see was his body, from the chest down, lying on his recliner. He wore jeans and basketball shoes. He sounded young.

“First time?” the faceless guy said.

“Yep.”

“Just keep gripping,” he said.

Anthony gripped extra hard on account of his high crits. His fingernails dug into his palm.

The faceless guy flirted with the snow-royalty nurses as they went round.

“Yolanda,” faceless guy said, “I’m not talking to you today.”

“Why not?” Yolanda flipped her long black hair while administering to someone else.

“You blew me off last Friday, that’s why not,” he said. “We were supposed to go for drinks. What happened to drinks?”

“I told you I had plans,” Yolanda said. “Besides, what would your girlfriend think?”

“She wouldn’t care.”

“Ah hah.”

Another girl walked by.

“When are we gonna go out and do something, Paula?” faceless guy said to her.

“I’m Erika,” the girl said.

“Erika, right, that’s what I said,” he said. “How about tonight? Let’s go out, you and me.”

“Are you gonna spend all your plasma money on little ol’ me?” Erika said.

“Hey, I got lots of money, babe,” faceless guy said. “I just do this to help the kids.” He gestured to a poster on the wall with a big smiling child supposed to have been saved by somebody’s plasma.

When the plasma bottle was full, a saline solution would be pushed through the tube into Anthony’s bloodstream.

“Just wait,” faceless guy said to him. “When that saline hits your blood it’s cold, man. I shivered the first time it happened. But now, hell, now I love it, it’s great.”

His bottle of plasma was almost full. He was ready for the saline.

“I’m almost done,” he said. “Here it comes!”

Just a couple more drops to go.

“Here she comes, baby!”

It did look like apple juice.

Across the room lay a 50 something year old man with bags under his eyes. He kept falling asleep. The nurses would smack his leg as they walked by.

“WAKE UP EVERYBODY!” they would shout.

Directly adjacent to Anthony was a young, maybe 20 year old guy, pickled and porky, with rosy cheeks and retarded eyes. His feet stood up at the end of his recliner like clown’s feet, huge and peanut shaped. Everybody was in this same position with slightly elevated feet, a disarming position. Everybody was on the same level: the bottom.

An hour later Anthony’s plasma bottle was almost full. A good looking nurse had just come on shift. Red hair piled upon a tiny head, not a single pore in her opal face, smart glasses that didn’t rest too high on her nose. She wore the same white smock that the rest of them had, but somehow hers was alluring.

“You’re almost done,” she said to him.

“Already?” he said.

The machine did its pathetic little “doot-doodooDOO!” The saline solution poured through the tube. It rushed like peppermint through Anthony’s veins. His whole right arm went numb, like menthol oil rubbed underneath the skin, directly on the raw muscle.

The cutie disconnected him. She put a piece of cotton on the tiny bite in his arm.

“Hold this here,” she said. Their fingers touched. How long had it been since that happened, he wondered. She wrapped him up and patted his shoulder.

“Good job,” she said. Then she handed him a white ticket.

“I don’t know how,” he said, looking at the ticket. “I’ve never done this before.”

“Come on,” she said, “I’ll show you.”

She walked him over to another machine. He wanted her to hold his hand.

“You put the number from your ticket in there,” she said. “Then you read the directions here.” Her arm and perfect little hand reached across his body to point at a sign on the machine. The sign instructed users in the proper method of entering your birth date on the key pad, which was the next step. He was too engrossed in her hand to read the sign, and so the first time he tried it, he did it wrong.

“Oops,” he said. “What?”

“Hit clear,” she sighed impatiently.

Finally, after three attempts, the 20 dollar bill slid out. He turned to smile at her, but she was gone.

He walked out the door and into the bright day. It felt good to be walking in the sun with a 20 dollar bill in your pocket. He breathed deep. A feeling, a good spirit flowed through him. He walked up Cherry Street and took a left on 22nd toward the outlet bakery.

Bio: Mather Schneider is a cab driver who divides his time between Tucson and Mexico. He has 4 full length books available on Amazon and has had hundreds of poems and stories published around the small press since 1994.