Songs From The Back Row is Phoenix poet Doug May's first full-length collection. The poems were written between 1985-2019 and are remarkably diverse in subject matter, theme, tone and style. The book consists of 57 eclectic outsider poems which strum the usual cords of an emerging poet- childhood reminiscences, portrait poems and the observation of everyday experiences through credible personal anecdotes. But what makes this book unique is May's uncanny ability to allow his readers to see ordinary things anew, as if from the eyes of a child living inside him.

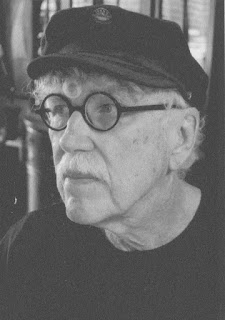

In the short biography on the back cover of the book Doug May describes himself as a "differently abled American." In the interview which follows this review, May was asked about what it was like growing up and how his sense of difference helped shape his writing. He says:

“I think there’s a book called Growing Up Absurd and that pretty much describes my childhood and adolescence. Because I spent all my time trying to imitate how other people acted and talked, even though it had nothing to do with me on the inside. I think this is pretty common among those with different brains, as long as the flaw isn’t too bad they learn to fool the outside world and pass themselves off as ‘normal’ whatever that means.

“I am someone who takes a little longer to learn new things, but I do fine once I settle into a pattern. I have trouble picturing stuff in my head, and counting backwards and stuff like that. And my short-term memory has always been dismal. But I’m not legally mentally disabled, and it’s not even certain that I’m ADD or ADHD, because I have some of the traits of those conditions but I can’t take Ritalin or Adderall. I had several friends who went off the deep end with anti-depressants and other mental painkillers, and at some point I decided to accept myself for what I was and not worry about weird EEG results or my low scores on the Stanford-Binet test.”

May’s self-assessment and his understanding of how other people view him make for a fascinating read and are at the core of what this book is about. It helps to establish his outsider status and the unique perspectives in which his poetry takes root and flourishes.

In the quintet ‘The Welder’ he is referred to as “the kid who took longer to/ learn his/ lessons”, in ‘Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ as having been dealt “a short hand”, in ‘Young Family On The Lawn’ as “the weird neighbor”, and as a pensioner in ‘The Wrong Side of 60’, as “weird and tall and/ out of place”. In ‘On The Borderline of Borderlines’ the speaker, presumably May, says that people are surprised because he can “act like all the other teeveeholics/ who go to Denny’s” or “shop on weekends/ at the mall.” He candidly admits, referring to his own eccentricities, “Some are better/ at hiding it/ than others.”

More interesting and revealing, in ‘Below Average’ a curious foreman wonders “if he really had an 86 IQ” and asks May to describe what his brain feels like inside. May’s response is unique, off the charts:

A foreman who saw

me scribbling notes

on my arm

and heard me

talking to myself

out loud

asked if it felt

dark and crowded

inside there

as the jungle

on a moonless night.

And I told him

no it was more like

the desert at noon

everything plain

as a cow's skull

picked clean

by graceful buzzards

no shadows

no angles

just meat

and rust

and sometimes

a few white bees

of rivers.

May says of the form and purpose of his poetry, " I don't know if I have a single purpose. Sometimes if I’m depressed and thinking inappropriate thoughts, I need to drown out the noise. Sometimes if I’m feeling good about myself I write in rhyme and meter like I learned from listening to my mother read poems like ‘The Cremation of Sam McGee’ or ‘Thanatopsis.’ I know that a lot of the closed form poems like the sonnets sound old-fashioned, but I keep doing them because if it’s good enough for Shakespeare it’s good enough for me—plus you always know where to break the lines.

"I try to be accessible, but I don’t think I have a particular reader in mind when I write. Ideally I would like to have the content dictate the form, but sometimes the content will work against itself to make something more interesting—even if it’s flawed.”

In the collection’s brilliant opening poem ‘The Junior Anatomist’s Demonstration’ May first explores the difficulty in defining a person’s intelligence through the narrow use of an IQ test. Gazing upon a collection of imitation body parts, he reflects on his identity, his place in the world and the notion of a soul as being unfathomable through reason:

And I always wondered

where I fit among that jumble

of parts laid out on the

teacher's desk: the pebbled sponges

of lungs and bright orange

croquet ball of the urinary bladder

with its ureters flexing

like irises, the eggplant spleen

squished tightly between

a cutaway heart and concertina

loops of intestines

and what the tests measured? Maybe

something so strange

nobody had ever actually seen it-

was the soul a place

that grew more distant the closer

you got to it or was it

like the red flowers

beneath your eyelids

hard to press between the

pages of a book

In the interview which follows, May says stoically of his experiences of being classified by psychologists as a child, “Actually when I was a young child, there was barely such a thing as ADD. In 3rd grade I scored in the borderline range on several IQ tests. So I got a lot of tutoring and instruction geared to slow learners. Later in my 20s they decided I was maybe ADD, but I had a bad reaction to Ritalin. One shrink told me that my ‘real’ IQ was probably in the 90-95 range but I tested lower because I had a learning disability.

“I feel like a number doesn’t totally define me, but on the other hand I’ve never worked anything but entry level jobs after college and I’ve had a lot of problems with mental health issues going back to early childhood. Coming from where I’m at, I have a tendency to expect things to always go wrong. But I cover it up pretty well and try to act positive. As somebody famous once said, you can only control your reactions to the world, not the world itself.”

The enigmatic poem ‘The Night Of My Last Cigarette Break’ further touches on the idea that there are some aspects of our lives which cannot be neatly packaged and explained. Some aspects, like memories don’t “retreat”, but pop up from time to time and need to be accepted “as hands folded in prayer”:

The Night Of My Last Cigarette Break

Nearly the middle of the week

And the first star twinkles

Like an ice machine

At the no-tell motel

Where runaways crash.

I have dined worked and slept

For months, unable to find

The honeyed sea of twilight

In which rooftops float

Like slender blue flames.

But now I stumble over

Something that doesn't retreat

Only to gather itself

In histories of false allure:

Not the stage whisper

Serving a legend's arc

And not the flame of urge

Crumbling into mansions

Of cellos and cobwebs

But staying true as

Hands folded in prayer

To what never was

And always must be.

(all poems posted with the permission of the poet)

In a recent email, May explained the context of the poem, "The Night Of My Last Cigarette was written when I was working the graveyard shift as a janitor in an office building. It was a job that I didn't have for very long but I liked it because it gave me time to think about poetry and life in general. The building was located downtown and there were a lot of street people and prostitutes of both persuasions wandering around at that time of night. The poem is about searching for meaning and something lasting and about saying no to addiction. The first version dates from the 1980s when I was attending informal workshops with Denis Johnson and Rick Barnes, another local poet."

Many of the people who inhabit May’s dozen or so portrait poems live on the margins of society and display insecurities, vulnerabilities and foibles. Some of most memorable include, ‘High Functioning’ about a 35 year-old woman who has a social phobia and only leaves the house to drive to work. In ‘Sanitarium In The Desert’ Brady is a violent patient with dementia. ‘Zanjera’ is a neighbour who carries a gun and is purported to have been born a man. In ‘Woman in Blonde Wig And Scrubs Robs Bank The Day After Christmas’ a thief uses a deadly culture from a lab to extort money from a bank. ‘At The Dealer’s’ May uses an extended metaphor to compare an ageing ex-mechanic with a car which has reached its use-by date. These are highly original character studies, from unusual perspectives and which are narrated through the use of credible anecdotes.

The collection is dedicated to Doug May’s mother and she appears in half a dozen or so poems. Although she died several years ago she still appears to have an all-embracing presence in the poet’s life. Despite her love, she is a quiet reminder to May of his own inadequacies and failures. In ‘Prohibitionist’ she is his “timeless conscience”, that even in death she returns to remind him that he is a drunkard like his father and his father before him, “Though vanished from the earth, she’ll find some way/ to fool the protocols of space and time/ And hover near my shaky morning cup./ She’ll know it isn’t coffee, never fooled.”

This idea of eternal surveillance is furthered in ‘Ghost’ in which May imagines that his mother is still fretting over him, saying under her breath “poor boy/ he tries”. In her heart he “remains a boy”, “an unfinished ball of clay” who still needs constant direction and spiritual guidance.

May says positively of his relationship to his mother, “My mother was just an average person, but she was remarkably determined. She spent hour after hour using flash cards and coloring books and every other tool she could find, trying to teach me what I would need to get along in the world. I was never college material but because of her I was able to attend college. She taught me good work habits and the importance of being punctual. And she encouraged my interest in poetry and music, even though she worried about me someday being able to support myself.”

The cover for Songs From The Back Row was created by publisher and painter Henry Grier Stanton after he read May's submission to Uncollected Press in 2019. The title of the painting was taken from May's title for the book and Stanton's abstract painting of a matador with an outstretched cape appears to have been inspired by May's poem 'Violence'. The poem ends:

no redder red than banks of

cold Christmas roses

silhouetted against

a bullfighter's cape.

Doug May says of the title, "It refers to how I stood in the back row for photographs or sat in the back row during lessons, because I was always the tallest kid in class. More generally it refers to being an outsider, somebody back in the shadows. I decided to call them songs instead of poems, because music has always been so important to me and my poems are often more like music than thoughts linked together logically.”

Some of the best poems in the collection draw on musical themes and this adds another dimension to his writing. In ‘The 9thInterrupted by Cell Phone’ May images his parents trading blows in the kitchen to Mahler’s 9thSymphony. Similarly, in ‘War Quartet (After Messiaen)’ he imagines POWs tramping to chamber music as orders are barked. In ‘A Consort Of Costumed Skeletons’ he imagines playing piano “vamping on/ the ivories” in a “hall of ghosts.”

Refreshingly, there are no poems in the collection explicitly about writing and only a few about the angst of relationships. May learnt the hard way decades ago that he is “different” and he has found it cumbersome relating to most people.

In the harrowing poem ‘Friday Night Dance at a Private Sanitarium’ May recounts how as “the slow kid” in Year 6 he danced but was “afraid to hold too close/ because something/ might go wrong.” In ‘Opposites Attract’ as a young adult he tries to make it with girl from the typing pool at work but it ends disastrously:

Opposites Subtract

When you were

the dishwasher blonde

from the typing

pool

and i was the

slowpoke janitor

who swapped

urinal blocks

at 3 AM

you taught me

how to keep track

of numbers in my head

and hide faded scars

beneath blindfolds

of desire.

But after we downed

a few lukewarm

margaritas

and paid for

a room

near the cactus

interstate

our births’

hardwired

accidents

left proving grounds

too wide

to cross- -

a lot of

wrong answers

earn half credits

but not when

the teacher’s a

freckled back

on a clean white

sheet

and the crackle

of a radio

in the next room

(because it’s what

you don’t say

about the weather

that can make

a lover stare

in disbelief).

We tried to ignore

the awkward pauses

and cling to

a few

salamander

clouds of

air conditioned

mirages.

But in the end

it was better

just to

pretend

the night

never happened.

May’s best poems simply let it rip- without over thinking what is happening on the page. He says of his writing process, “My poems often begin as dreams, sometimes I get up at 2 AM and write down a dream and then I use the dream months later. Sometimes it’s just a single image or a series of images because I think in images and sounds instead of logical concepts. I’m very much into sound, I don’t care if a poem makes any logical sense as long as it has rhythm and color and something lively going on, not just dead words on a page.”

When asked where his poems come from, May says candidly, “The things that pop into my head when I’m writing often amaze me, because I have no idea where they come from. On the other hand, poetry is the one place in the world where I can be completely and totally myself. Maybe the brain is like the universe, mostly dark matter with a little light squeezing through. I don’t know why I do it, I just know that I must do it or risk feeling hollowed out and hopeless.”

As a consequence, when you first flip through this book you will quickly discover that the subject matter is extremely diverse and full of delights and surprises. To name a few, in ‘Jimmy’ the speaker befriends a cockroach, in ‘Condemned Lot’ May uses sonnet form to describe a barren desert sump within suburbia, in ‘The Lost Pets’ he creates a poem from the point of view of an animal after seeing a sign on a power pole and in the rhyming quintet ‘Transformation’ May charts a war with invading talking insects.

A personal favourite, is May’s poem ‘Potatoes’ which is bursting with invention, intricate poetic word play and good humour. It uses striking metaphors and personification to transform the humble spud into a polished work of art. He says of this piece, “Potatoes I worked on and off on for twenty years. It started out as a short rhymed poem toward the end of the 1970s and just kept growing and becoming more serious without losing its humorous essence. It’s one of the few long poems where I try to be clever and self-referential and even indulge in a bad pun or two. And it addresses a topic that I largely avoid these days – the conflict between art and life, and the artist’s ‘privileged’ viewpoint verses the joys and rewards of everyday existence. I remember there was even a reference to Harold Bloom in one of the early versions.”

Potatoes

I know what time it is,

it's time for potatoes.

See the meat crouching

in its pan, the carrots

in their skinny glass

boat, and here here

are the potatoes-

bald as lamas but

soon to be bearded

with gravy next to the

green pencils

of northern beans.

Yes and I will eat them

as I have since childhood

never admitting how little

I love them, how all these years

I have fooled them by

Swallowing the wafers

of a faith I must embrace,

secretly resenting their

smug pilgrim plainness

and how they congregate

around beige vacancies.

I know what it is, why

they annoy me so much -

they resemble too much

the carefully chosen guests

at a dinner meant to

impress a stranger.

It is during such times

that they become useful,

the predictable ones who

occupy space and even

make conversation

when they're certain

no one is listening.

Such usefulness can be

respectful but never loved.

A roast or stew stands out

when it's flanked by

baked or boiled spuds

just as talent tastes richer

when it's surrounded by

critics' empty calories.

Yet genius and stew

may be praised without

their hangers-on, and

no one would think to trade

a good trussed fowl

for its cloistered tribes

or mashed or glazed

admirers. Still it is potato time

and still I am filled

with doubt- even knowing

the uses of Solanum tuberosum

and realizing the weighty

obligations of potatohood:

to balance the platter,

orbit the steamy roast,

play second fiddle to

delicate spinach or peas.

If I truly believed that less

meant more than the mirror

keeping score, I would

forbid myself the bland

comfort of potatoes--

even after January passes

and resolutions do the way

of soggy crudités.

But maybe there is wisdom

in saying yes to them

or the world in which

they matter, in sinking down

into the solemn gravitas

of roots and clinging soil.

And since real satisfaction

must wait on what comes

after dessert, I will return

to their blunt myopic eyes

and wrinkled russet skins

and praise them with butter

for how they remind me

of all the midnight burger runs

at which I only asked for

extra mustard and onions

and a dog with mournful eyes

begging fries at my feet.

Doug May's first full-length collection of poetry Songs From The Back Row is a rich and enjoyable book to read. It has variety, depth and elements of mystery which will keep you entertained, intellectually stimulated and greatly amused. Doug May has cleared many challenging hurdles to bring this gift to us.

INTERVIEW WITH DOUG MAY 28 MARCH 2020

When did you start writing poetry seriously and when were you first published?

I have written rhymed doggerel since I was nine or ten years old. But the first poem I wrote that I really considered serious was something called “The Truce.” The main event in the poem is an undeclared truce that occurred during the battle of Anzio. It was a terrific story told by one of my uncles who was actually there when it happened. And North Dakota Quarterly published it back in the early 80s. I was very proud at the time. Now I don’t even own a copy of the book with my poem in it, because I’ve lost it along with a lot of other stuff.

Who were some of your early influences? More recent ones?

The Bible and Shakespeare. Patty Smith and Bob Dylan. ee cummings. Recently I have gotten into Alfred Starr Hamilton. And of course, Denis Johnson, a wonderful and under-appreciated poet. I knew him briefly in Phoenix in the 1980s when he was going to AA meetings and writing his novel “Angels.” He told me I had talent, which made me start to take my poetry more seriously.

The back cover mentions that as a child you were treated for ADD, behaviour issues and depression. You received a great deal of educational intervention and eventually went to college. How did these experiences shape the sort of person you are and your writing of poetry?

Actually when I was a young child, there was barely such a thing as ADD. In 3rd grade I scored in the borderline range on several IQ tests. So I got a lot of tutoring and instruction geared to slow learners. Later in my 20s they decided I was maybe ADD, but I had a bad reaction to Ritalin. One shrink told me that my “real” IQ was probably in the 90-95 range but I tested lower because I had a learning disability.

I feel like a number doesn’t totally define me, but on the other hand I’ve never worked anything but entry level jobs after college and I’ve had a lot of problems with mental health issues going back to early childhood. Coming from where I’m at, I have a tendency to expect things to always go wrong. But I cover it up pretty well and try to act positive. As somebody famous once said, you can only control your reactions to the world, not the world itself.

Since I don’t have the kind of brain to write short stories or novels I guess I’m stuck writing poems. But I don’t regret this at all, I’m just thankful that poetry exists.

Do you write everyday or do much editing?

Yes, I am always jotting down images and ideas that I can later shape into poems. Rarely a new poem falls into my lap that doesn’t need fixing. Like “Conservation of Energy.” But I do a lot of editing, and it is very haphazard and jumpy editing because of my brief attention span and trouble concentrating. But I do work on poetry every single day usually in short bursts.

How do you begin a poem?

My poems often begin as dreams, sometimes I get up at 2 AM and write down a dream and then I use the dream months later. Sometimes it’s just a single image or a series of images because I think in images and sounds instead of logical concepts. I’m very much into sound, I don’t care if a poem makes any logical sense as long as it has rhythm and color and something lively going on, not just dead words on a page.

What's your purpose in getting it down on the page?

I don’t know if I have a single purpose. Sometimes if I’m depressed and thinking inappropriate thoughts, I need to drown out the noise. Sometimes if I’m feeling good about myself I write in rhyme and meter like I learned from listening to my mother read poems like ‘The Cremation of Sam McGee’ or ‘Thanatopsis.’ I know that a lot of the closed form poems like the sonnets sound old-fashioned, but I keep doing them because if it’s good enough for Shakespeare it’s good enough for me—plus you always know where to break the lines.

I try to be accessible, but I don’t think I have a particular reader in mind when I write. Ideally I would like to have the content dictate the form, but sometimes the content will work against itself to make something more interesting—even if it’s flawed.

What were the processes which were happening behind the scenes which got your book published? What was Hank Stanton's involvement in the project?

Well, since 'The Truce' I have sent out my poems occasionally, and sometimes they are accepted and 90 percent of the time they are not. I don’t get depressed about it, I just keep plugging away. With Hank, I guess he was my ideal reader, because he accepted my first submission to Raw Art Review in less than two hours after I’d sent it through Submittable. So the lesson is, don’t give up. You only need to find one editor who is enthusiastic about your work in order to gain acceptance and maybe even win a contest and have a book published.

Turning to your book of poems Songs From The Back Row, how did you arrive at this title?

It refers to how I stood in the back row for photographs or sat in the back row during lessons, because I was always the tallest kid in class. More generally it refers to being an outsider, somebody back in the shadows. I decided to call them songs instead of poems, because music has always been so important to me and my poems are often more like music than thoughts linked together logically.

What role has music played in your life?

It was obvious that I was musically talented from an early age, and I was given music lessons and encouraged to improvise little pieces at the piano. I can play from notes and also by ear. I was classically trained for 8 or 10 years, and I have accompanied other musicians, played in a rock band and a jazz combo, and performed classical solo repertoire until I started having problems with my hands a few years ago.

After reading your book publisher/ artist Hank Stanton of Uncollected Press created the cover of the book. It appears to be based on your Imagist poem 'Violence' which ends: "no redder red than banks of/ cold Christmas roses/ silhouetted against/ a bullfighter's cape." Is this the case?

Well you’d have to ask Hank. But I think that’s a really smart observation, and it made me look at the cover art in a different way. If he was turned on by that particular poem to make that particular abstract picture, I think it’s a great example of how words and images can inspire each other on a deep irrational level.

I notice the book is dedicated to your mother and she appears in some of the poems. What sort of person was she and what effect did she have on your life?

My mother was just an average person, but she was remarkably determined. She spent hour after hour using flash cards and coloring books and every other tool she could find, trying to teach me what I would need to get along in the world. I was never college material but because of her I was able to attend college. She taught me good work habits and the importance of being punctual. And she encouraged my interest in poetry and music, even though she worried about me someday being able to support myself.

Your poems build up a profile of you being a weird and tall and borderline kid who has a difficult time relating to other people. What was it like growing up (as you refer to in your bio) as a “differently abled American?” Has your condition ever been properly diagnosed? How has your unique perspective helped shape your writing?

I think there’s a book called Growing Up Absurd and that pretty much describes my childhood and adolescence. Because I spent all my time trying to imitate how other people acted and talked, even though it had nothing to do with me on the inside. I think this is pretty common among those with different brains, as long as the flaw isn’t too bad they learn to fool the outside world and pass themselves off as “normal” whatever that means.

I am someone who takes a little longer to learn new things, but I do fine once I settle into a pattern. I have trouble picturing stuff in my head, and counting backwards and stuff like that. And my short-term memory has always been dismal. But I’m not legally mentally disabled, and it’s not even certain that I’m ADD or ADHD, because I have some of the traits of those conditions but I can’t take Ritalin or Adderall. I had several friends who went off the deep end with anti-depressants and other mental painkillers, and at some point I decided to accept myself for what I was and not worry about weird EEG results or my low scores on the Stanford-Binet test.

The brain adjusts to its quirks and shortcomings. I was usually able to work unskilled jobs, sometimes more than one job at a time to afford living on my own. I’m just glad that I’m not entering the work force now. Because I’m terrible at multi-tasking and I have big problems figuring out anything with numbers. Like I could never learn how to operate a cash register without making mistakes, no matter how hard I tried.

What do you wish to achieve through your poetry?

Maybe it would be more accurate to ask what is poetry trying to achieve through me? Because the things that pop into my head when I’m writing often amaze me, because I have no idea where they come from. On the other hand, poetry is the one place in the world where I can be completely and totally myself. Maybe the brain is like the universe, mostly dark matter with a little light squeezing through. I don’t know why I do it, I just know that I must do it or risk feeling hollowed out and hopeless.

How's your memoir coming along?

I finished the first draft but it’s really disorganized and needs a lot of editing. I don’t think I’ll ever try to publish it. But I keep using it to trip start my poetic impulse. Maybe I don’t know what day of the week it is or where I parked the car twenty minutes ago, but I can remember the smell of a favorite stuffed animal when I was eight years old. The brain is mysterious.

Thanks Doug for taking the time to answer my questions.

I am honored that you are putting so much work into this. I hope you, your family and friends are staying healthy during this time of stress.

Biography: DOUG MAY has been treated for ADD, behavioral issues and depression. As a child he received a great deal of academic tutoring geared to his abilities (including piano lessons), and eventually earned a GED (General Education Diploma) and went to college. He was worked many entry level and unskilled jobs- everything from proofreading children’s books and data bases to stocking shelves, driving a delivery truck, moving furniture, selling music, emptying bedpans and performing at NCO clubs in a rock and roll cover band. He is currently retired and working on a memoir about his experiences as a differently abled American.